Tales From the Night Rainbow

By Pali Jae Lee and Koko Willis

Kaili’ohe’s stories of the ancient people, an oral history of Hawaii before the Aliis invaded.

History, as anything else, is seen and understood by where a person stands on the mountain.

All people climb the same mountain. The mountain, however, has many pathways – each with a different view. A person knows and understands only what he sees from his own pathway, and as he moves, his view will change. Only when he reaches the top of the mountain will he see and understand all the views of mankind. But who among us has reached the top of the mountain? Tomorrow, we too will see a different view. We have not finished growing.

Most Hawaiian histories have been written from the pathways taken by foreigners who wrote Hawaiian history as they saw and believed things to be. It was not a Hawaiian view, or from a Hawaiian pathway. These stories I tell you are from a pathway taken by my family, on Moloka’i. They are the stories as told by Kai-akea to my teacher and beloved mother Ka’a kau Maka weliweli (whom I will refer to only as Maka weliweli) and she in turn taught to those of us who were part of her halau (school) in Kapualei.

The ancient ones were the people who were maoli (native) to Hawaii. Seven or eight hundred years ago the Tahitians came to our islands, and since then the stories of our origins and life have been dominated by their outlook. In many ways the Tahitians were a people similar to us, but in other ways we were as light is to the dark. The early ones lived with an attitude about life that gave them what we would call great mana (power) over their surroundings, but it is really the power of love and kinship working through the feelings of the objects we live among.

Our ancestors lived in small family communities and were guided by the elders of the family. The families were called ‘ohana, and all of the families on the islands who were of our line were ‘ohana laha. Today we would call that a clan. There were many clans in those days and many people. Different communities belonging to a clan wore kapa (clothing) of the same color, but they had different markings on their kapa, to show to which part of the clan they belonged. When someone met a stranger and he wore the family color, he could tell to which branch of the family he belonged by these differences.

Each family had what we call an ‘aumakua, a spirit felt as a living part of the family – a presence – like our ancestors, aware of us and ready at all times to show us the turns in our pathways. This spirit could be a part of anything or everything. Our family was a mo’o family. A mo’o is a giant lizard or dragon, however, we were kind to all creatures for they were our brothers. We felt more for the lizard because it was our belief that they brought us luck, protected us and watched over us.

Our family wore our hair shoulder length and the men wore short beards. Some other branches of the family cut their hair short and plucked their beards. All the descendents of Kanehoalani (the Kaiakea family) wore finger tattoos to show that we followed a holy life. Other branches of the family had other tattoos, and some wore no tattoos at all.

There were many clans in ancient days, each with its own color and its own ‘aumakua. There was the shark family with its colors of grey. There was the shell clan who wore a dark red, and the owl family who wore kapa of browns. The thunder clan of Maui wore only the darkest black. On O’ahu there were families who wore orange (Leeward families) and in Koolauloa there were families with beautiful pink kapa. There were three very different and beautiful red kapa: the Kanekapa, Ke kupa ohi and Ke akua lahu.

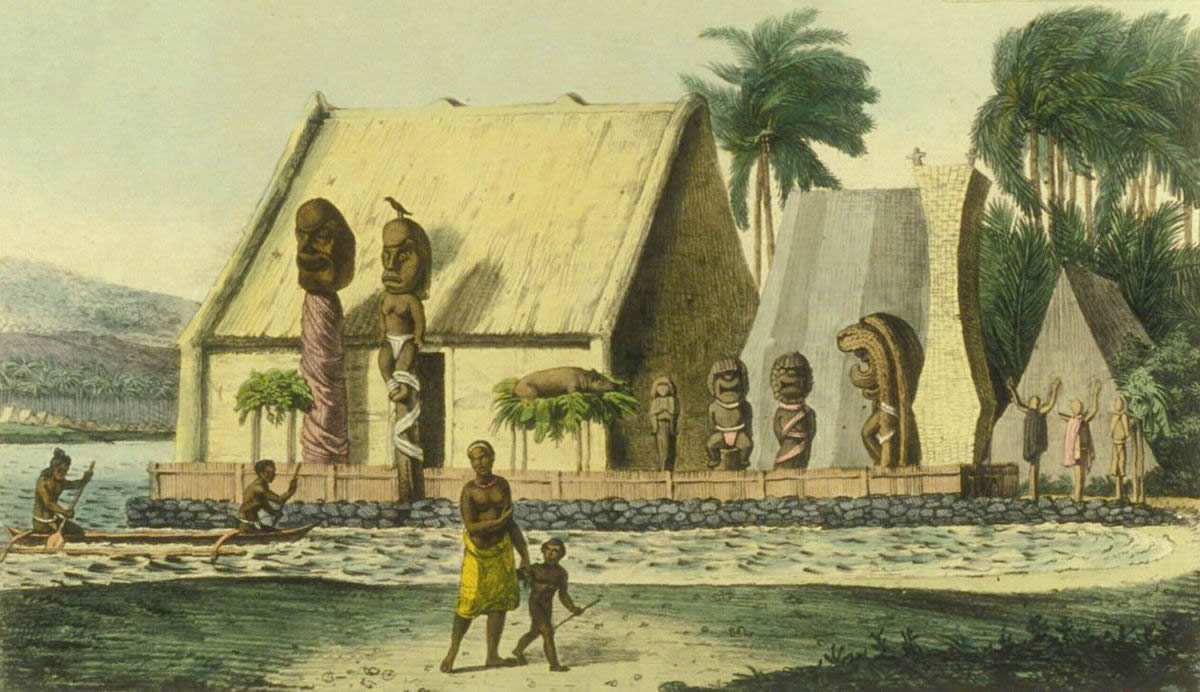

On Moloka’i the gods were Ku and Hina. The temples (heiau) had an upright stone for KU (the male god) and prostrate flat stone for HINA (the female god). The temples of our family had a light which burned at all times and someone was always there to tend to it.

It was the belief of our family line that we had been here from the beginning. People had gone out from our land to the East and to the West, and populated other lands. We had chants that told of such migrations from our islands.

We taught by stories and parables. One of the earliest and most important to us was:

“Each child born has at birth, a Bowl of perfect Light. If he tends his Light it will grow in strength and he can do all things – swim with the shark, fly with the birds, know and understand all things. If, however, he becomes envious or jealous, he drops a stone into his Bowl of Light and some of the Light goes out. Light and the stone cannot hold the same space. If he continues to put stones in the Bowl of Light, the Light will go out and he will become a stone. A stone does not grow, nor does it move. If at any time he tires of being a stone, all he needs to do is turn the bowl upside down and the stones will fall away and the Light will grow once more.”

The stories or parables were teachings and reminders. The maoli had stories of vines, trees, seeds, fish, earth, sea and sky: the things that were common to the people and that they understood. When a child began to speak, the family began to teach him about the world of which he was a part.

- Aloha is being a part of all and all being a part of me.

- When there is pain – it is my pain.

- When there is joy – it is mine also.

- I respect all that is as part of the Creator and part of me.

- I will not willfully harm anyone or anything.

- When food is needed I will take only my need and explain why it is being taken.

- The earth, the sky, the sea are mine tTo care for, to cherish and to protect.

- This is Hawaiian – This is Aloha!

The ancient ones believed that all time is now and that we are each creators of our life’s conditions. We create ourselves and everything that becomes a part of our lives. Any situation in which we might find ourselves is brought about by learning the many pathways of life. When we wish to change our circumstances, all we have to do is release our present condition. It will be gone. On the other hand, if we find it useful to continue, we can hang on to the problem and not let it go.

The early ones believed that there was one body of life to which we belonged. We had land, sea and sky. They, too, were a part of us. Everything that grew on our land and swam in our ocean we called brother and sister. We were a part of all things and all things were a part of us. The old ones knew this and lived accordingly. They did not destroy. They spoke to a plant that was to be picked and explained why it was being done. A rock, before being used as a part of a new house platform or heiau, would be asked if it approved of being used in such a manner. If signs were against such use, the people needing the rock moved to another location and asked a different rock. It was far better to do something correctly than in a hurry or without regard for the effects of our actions.

Na Ali’i: The Chiefs

To us, they were invaders. Pa’ao had gone back to Tahiti and gathered thousands of people to come to Hawai’i and take over the land. The men were tall fierce warriors. They did not believe in the force of light, only in the force of the closed fist, in mighty armies that killed, took and plundered.

The people on Lana’i were the first to see them approaching. They said the red malo of the invaders could be seen from horizon to horizon making the sea itself take on a red hue. Soon the sea did turn red with the blood of our people as thousands were slaughtered and enslaved. The native population that could, made a run for Kaua’i where they would he safe. You had to be well schooled in the tides of Kaua’i to get ashore safely. Many of the people who could not get to the boats in time hid in mountain caves. The people who were caught were used as fishbait and human sacrifices, and their bones were used to decorate the tiki statues of the Tahitian gods.

The Tahitians who became the rulers of our islands called themselves na ali’i (the rulers or chiefs) and they called our people Mana hune (small power) because they thought we were a joke. In fact the people who lived here before the ali’i came were much smaller than these warriors, and had no knowledge of how to use a spear of club or any manner of war weapon. The early people had used their minds to cooperate with the world and had no war leaders or chiefs to lead them into battle. They were fishermen and farmers. They shared all they grew and caught with the community. To be a warrior you must be trained in the ways of war. No one in our Islands had such training at that time. Since the Tahitians did not consider mind power to be power at all, the people were as they said – Mana hune (small power).

Some of the people who were living in the Islands at that time were the descendants of Menehune, a man who had 16 sons. The two names merged and all people who were here before the Tahitians took over our islands were called the Menehune. In truth there were many different lines of families before the Tahitians. As a group they called themselves the Mu and the Islands the Mu also. Individually family groups were known by their own name. On Kaua’i there was the Kama kau po and the Nawao. On O’ahu the Lae and Pae and Kea families. On Maui there were the Ahu and the I families as well as many Lae family members. Some families were just known by their ‘aumakua and nothing else.

The people on Moloka’i who were my ancestors called themselves Ka Po’e Ao Hiwa (the light carriers, or the people who tended the Sacred Light). Other families on Moloka’i had names to do with the Light or the Rainbow.

Legends and stories of the Menehune’s great deeds came about because the ali’ i would give orders when they wanted a fishpond built, or a temple or a ditch, and allowed a very short time for it to be done. The ali’i would order the maoli (natives) to do the job and go off laughing. If the work was not accomplished in the given time, all the people of that place would be slaughtered.

When such orders were given the maoli or pre – a/i’i came out of hiding – down from the mountains, from the caves – and they worked together as one person to accomplish the task. These jobs were done at night because during the day other work had to be done. When enough people were not available on one island, fireballs were sent up as a signal to the ancient ones on other islands that help was needed.

When the first rays of dawn began to show on the day the project was to be completed, the boats were already gone. The people had returned to their caves and mountains. There was no sign of anyone. Since the ali’i knew it was not possible for the people of that certain site to do the work by themselves, they thought the ghosts of their ancestors helped them. When they happened to see or hear people coming down from the mountains for such a project, they hid, for the burial places of the ancient ones were in the mountains. This is how the stories of the night marchers began. In those days, the ones who marched were flesh and blood. They would not bow to the rule of the blood thirsty ali’i so they hid away, waiting for a time when the land would be at peace again. Some families lived several generations in the mountains before they knew things would not change back to the old ways, ever again.

The ali’i people ruled through a system of chiefs. War was accepted as a way of life. They thought everything could be taken by force. They were always fighting – brother fought brother, father fought son. They had no peace in their hearts, and as it is with wars, no one won, for with wars, all lose.

On Moloka’ i we were not bothered as much as people on other islands but we had our time of trial also. The ali’i feared the people who lived on Moloka’i for they thought all who lived there had great personal power.

The reason for this belief was that when Pa’ao’s warriors came to invade Moloka’i’s shores they found the people standing there waiting for them. They did not run. They stood together as a silent army. No fist was raised. When the warriors began to beach their boats the chanting began. It began small and became a mighty roar. The warriors threw their spears but they fell short of hitting anyone. Men trying to come onto the beach were falling back into the surf choking, unable to breathe. They did not invade Moloka’i’s shores at that time. They called Moloka’i – Pule-o-o (powerful prayer) and this was brought back into being many times through the centuries after that.

In time there was mixing of blood. The lines that had more of the pre – a/i’i blood were called sacred and the chiefs who had such blood were called the sacred chiefs. Tahitians came to conquer our islands and in many ways were conquered themselves. They took many of our chants as their own. They took many of our teachings and our parables. Many ali’i came to Moloka’i and walked among our people as friends or family. They gave us no orders. Some of their children were raised by the learned ones on Moloka’i so they would know all things. Some of these men grew to be great chiefs. Some still saw more glory in battle than in awareness and love and their bodies died in battle for they had much to learn. Although some returned to their warring ways, others did not.

To us they were invaders. They took our women and our heiau. They felt free to walk among us and take our food or whatever they desired. They gave us orders and called us commoners. We were not commoners. We were the ancient ones who had lived here many generations before they invaded our shores with their red malo. They came to conquer with raised fists and war clubs. Many would learn new ideas and put down their clubs to pick up a simple bowl of light.

The System by Which the Family Ruled

Although we lived in a communal society and much of the family possessions were owned by the whole community, each individual’s personal possessions were treated by others with the greatest respect. A person’s belongings were seen as part of himself and to trespass on his possessions was to violate the man himself. To steal from someone was to take part of his mana (personal power); therefore anyone who was a thief was expelled from his family. No mistake or crime (crime being a haole concept) was seen as worse than this. A person might suddenly become angry with another because of misunderstanding. He might strike out at someone, and a fight take place. This was understandable. To steal, one first had to plan. and the taking was a deliberate act against another.

The ali’i put thieves to death; we did not. The fear of banishment seemed to work for us, for few were ever guilty of stealing. The few that were, during my lifetime, were frightening for me to see. They were told at a meeting of the entire family that from that time forward they did not exist. They would not he spoken to. They would be ignored and even if they were to walk among us, they would not be there. They were now kauwa. They were dead to us. In fact, they were less than dead, for we honored our family in spirit. The outcasts just ceased to be. Some of these people would throw themselves into the sea to die; others left and were not seen again. We never spoke their names, so we could not ask family, or people of other families, if they had been seen. This was an old rule of the family system and not challenged to my knowledge. This law of ceasing to be, was a very powerful one. We needed no other.

When a child was born, he was presented with a mat and finely beaten kapa by his family. These would always he respected as part of himself. As long as he lived no one would step on his mat without permission or touch his kapa. At times a person was given permission to sit or sleep on another person’s mat. A person never crawled beneath another’s kapa. Each person lay down covered by his own kapa covering. Whenever a person traveled – when he went to war, to the Makahiki games, on a business journey, or anywhere else – his mat and his kapa always went with him. When he died, they were burned.

For two people to share a mat beneath the same kapa meant they were married. When it was a love affair from a chance encounter a mat might be shared but not the kapa. Sharing a kapa had to he acceptable to both the man and the woman.

As a rule, the calabash or bowl of an individual was not touched by others, but there were exceptions. The elderly in the family were far more strict about their bowls than the younger members of the family. They had learned and seen people become ill from this, and considered it a bad omen. The sharing of the large poi calabash, and container of fish was done by all. It was only the individual small calabash that was kapu.

The elders of the family had several mats and kapa as well as their calabash. These were often cared for by one of the younger members of the family. With the ali’i, each chief had a younger brother or a son of a brother carry his calabash, his spittoon and his hair and fingernail clippings as well as his many mats and kapas. This person could walk in the shadow of the chief and the honor was tremendous.

Our family was not ruled by the a/i’i chiefs except indirectly. We were ruled by our elders or kupunas, for they had lived longer and were wiser. Among these elders were the masters of the family – the kahuna. The elders of our family handled all disputes within the family. They also handled problems family members had with someone from another family, or with the ali’i chiefs.

The family colors were of the utmost importance to family members. This was true of our family and every other family, ali’i or maka’ainana (a person not of ali’i blood – literally the eyes of the land). Our colors were our identity – our pride.

To use the color of another was foolish. It could be the color of an enemy, or a line superior to your own and it would only invite trouble. To use a color that was not your line said you had no family pride. The family color was sacred.

Within the family all first cousins, sisters and brothers and half-sisters and brothers were simply called sisters and brothers. All of the generation of the parents were called makua (parents). All people of older generations were called grandparents. We called them kupuna. Individually they were called Tutu and their given name. We loved them all, for they first loved us. When you did not know the genealogy chants of your family it was extremely difficult to know which pair of these many kupuna were your individual line. To most of us it didn’t really matter. A child did not belong to one set of parents but to all the family.

To tell our parentage, or the line of family, we used an “a”. If I was speaking of my mother’s line I would say Kaili’ohe a Ke-kau-like a Lunahine. If I was speaking of my father’s family I would present my grandfather first and then my father – Kaili’ohe a Kai-akea a Pe’elua. If I did not know who the blood parents were I just stated the grandfather’s name. Many people on our island had names with a Lae for the great line of Lae, many had a Kea for that line, and many used Mahi for the line of the Mahi chiefs. These were the three main lines left of the old ones, who had lived on Molokai so many hundreds of years before the Tahitians came to our shores.

When Kaui-ke-a o-uli (Kamehameha III) declared the Great Mahele and the land began to be divided among the chiefs, Gerritt Judd suggested to the king that all Hawaiian people be made to take family names. Many of the people did not understand however, and mix-ups were many.

Many people did not know who their actual father was and many questions arose around family circles and, in our family, a lot of giggling. It seemed so silly.

The Hawaiians believed that land could not be owned by an individual. They shrugged their shoulders when the ha’ole came to the Mission Station to explain what was being done. “More foreign nonsense” was the general opinion. When someone offered to give a few yards of cloth or a jug of wine for the title paper to the land many said “Why not?” The exchange was made. It was not that we were stupid. It was not that we were illiterate, for most of us could read and write. It was a total lack of understanding between two cultures. In our family, we collectively owned many things. Very few things were individually owned. The land. the sky, the sea, were for all men. How can you divide that?

With all these changes the old family system of rule was thrown aside and new ways introduced. The new ways were foreign ways and useless to the Hawaiian heart. It left the Hawaiian without identity. He lost his family, his way of ruling himself, his history and his dignity in a few short years, all for the lack of understanding.

At the same time, the Hawaiian children were being taught a history in the government schools that had nothing to do with the memories of the kupuna (elders; grandparents) of the families. Government schools at that time were taught by the missionaries and their point of view prevailed. It was the view of the teachers from where they stood on the mountain. They did not see the Hawaiian point of view. In fact, in many cases, they did not see the Hawaiian at all.

The children of the islands were being taught that their ancestors were cannibals. This was not the case – not with the ali’i and certainly not with the pre-ali’i. The ali’i did have human sacrifices during the time of Pa’ao, and there were many during Umi’s terrible reign. There were also many ali’i chiefs who put no one to death. Children were taught, however, that their ancestors were cannibals. lazy, and played all the time in the water and in bed. Teachers used the word indolent, a word never explained to me, but it had a very nasty sound.

I wish we had more hours to play in the water. I wish we had more time for rest and love-making. All of my life, my people worked very, very hard. We did not ask another to do for us what we could do for ourselves. We shared all we caught, grew and made. We wasted nothing. To waste or take what was not needed was great error and the person would he called upon at some future time to right the wrong.

It was my belief that the ‘Ohana system was the originator of what was later called the Aloha Spirit, for all life was founded on love. There was love of family, love of land, love of sea, and love and respect for yourself and all around you! All were one!

It was difficult for people to understand the family ways of yesterday. For instance, few can understand the fact that one household had so many wives. The Hawaiians have been talked about as if they had harems.

The concept of wife, and of family were very different from what they are today. It has always been the custom for Hawaiians to care for one another. When a man died what was to happen to his household? Who would care for the wives and children left behind? They were taken into the household of another (brother, son, cousin) as wives with all the rights and privileges they had in their own home. If they caught the eye of another, and wanted to leave, they had the right to go. As a rule, no woman was kept against her will. I know of a case or two where a man wanted very much to share the kapa of a certain wife newly acquired from the death of another. The woman would not accept him, and in one case when she wanted to leave to marry another, he was consumed with jealousy and refused to let her go. This was not usually the case, however.

Some of these women were old enough to be grandparents of the men who took them into their households as wives. Then, as now, men want romance with a pretty face and a young. shapely body. Most romances were with beautiful cousins of equal rank, a comely commoner, or to carry on the blood line, a sister to produce an heir of the highest blood line.

There were occasions when a brother and sister truly loved each other. Usually it had nothing to do with love. The sister would be kept isolated a month or so before the coupling took place with the brother. After that (sometimes before as well) she was allowed her own husband and her own household. That she was having children by two men at the same time seems strange to people now, but it was done in an orderly fashion. It was not a running from bed to bed kind of business.

When a man wanted to take a wife, but it left a sister alone, or an elderly mother, this person would be taken into the household also. Some of these women lived out their lives without sleeping with that man. Sometimes their stay would be a few months or years until they saw someone they wanted and who wanted them, then they moved on. While they were in the confines of his home they were called “wives”. Women, ali’i and commoner alike, always had the right to refuse to bed with a man. This pertained even to sisters who were to carry the blood line. Sex was not seen as something a man could demand and the woman had to submit. They were equal in the meeting and sharing of the responsibility.

Some women would flaunt affairs they had with high chiefs. A child born of such affairs was sometimes taken into the household of the child’s father, and at times the mother too (not as a wife of any station, but the comforts were there just the same). High chiefs also used their high rank to claim the favors of young girls. Keawe-kekahi-ali’i-o-na-moku (a high chief of Hawaii) was noted for spreading his seed throughout the islands. It is often said that no man walks in Hawaii nei that does not carry the blood of Keawe-kekahi-ali’i-o-na-moku in his veins. With him, I think ali’i and commoner alike were afraid to say no when he requested favors. He was a fierce warrior and not one who bothered with the feelings of others, regardless of their station in life.

There were many kind ali’i. One of the best was Kamehameha-nui, ruler of Maui. When he died he passed the rule to his younger brother (not to sons) Kahekili, and technically, all his wives, and wives still in the household that had come from the household of their father Ke-kau-like, went to Kahekili also. Some of Ke-kau-like’s wives had died and others had new husbands but some remained. Namahana who was the sacred wife of Kamehameha-nui refused to go. She had her own lands, kept her own council and kept the wives of Kamehameha-nui and Ke-kau-like with her. The reason she gave was that Kahekili who was now 59 years old lived too quiet a life for her. Namahana was full of fun and gaiety. She loved to party and gamble. Her household was full of guests and drinking all of the time. If she were to go into Kahekili’s household all that would end. He lived a quiet life. He had two wives, spent his time swimming and surfing and did not even drink liquor. Kahekili was angry with her, for her lands by right were now his, for they had been his brother’s. He had a few choice things to say about her, but he let her go her own way. Kahekili took no other wives when he became high chief. He once stated that had he known in his younger days that some day he would rule, he might have wooed a few pretty young girls. He was an excellent sportsman but a reclusive man. He never drank of the ‘awa root, and he spent hours walking beside the ocean, swimming or diving with only one or two male companions.

Family, to us on Moloka’i was seen as a solid unit. A whole, of which we were each a part. In actuality, the family was a community or group of people living together, growing together, working out their problems the best way they could together, all connected, all learning and growing and assisting each other in their growth. We were all related in some way. Many generations – many fingers of the same hand; parts of one body.

Each ‘Ohana was governed by a group of kupuna (elders) – Age alone did not make one a part of this group. There were many old people who were not. To become part of the ruling body of the family you had to be accepted by all of the elders. Everything was decided on consensus of opinion. The ruling body varied in size, and always consisted of kahuna (experts) of many kinds.

When a person proved himself through years of hard work and wise thinking, if they were known for being loving and unselfish in all things, and had mastered many of the family secrets, sooner or later their name would come up and the kupuna would discuss making this person a part of their group. No vote was taken. If everyone was in agreement, then at the family ‘aha (meeting) they were requested to join the other kupuna who ruled on the upper part of the circle. It may sound simple. It was not.

One of the kupuna was our chief or ruling elder. He did not rule alone like the ali’i. All our ruling elders ruled together. This one person met with other family heads when there was need of it, and brought us news of what was going on in other families.

The ali’i had ruling elders, too, but they were not of the family line. They were the political supporters of the chief who had appointed them. These ruling bodies were called councils, and later after the foreigners came they called them the Privy Council. Most of the members of these bodies were men (for they fought the wars), but on occasion there were women appointed to serve. Ka’ahumanu was given the seat her father had held in the council when he died – Many ali’i women had served before in other councils, and the women who were regents after her death had important places in the council.

In our family line it was possible to serve in more than one family council. Maka weliweli served in her father’s council before his death; she was a member of our kupuna (elders); and served in family councils for two of her brothers. Maka weliweli was a teacher and a mystic so was not always around when a family council was held. When she was with us she did not always choose to sit with the elders. If family members wondered why this was they kept it in their own hearts and did not ask questions.

Family members did not question the family council. The decisions they made were considered law and the family abided by them. They had the greatest mana and knowledge. For this reason they were our leaders. We did not argue with them, even if we disagreed in our hearts.

The kupuna ruled at all ‘aha (family meetings) and ‘aha’aina (meeting where food was served). They handled all disputes within the family and problems family members had with outsiders. When an ‘aha was called, no one questioned going. The rule was – if you were alive, not dying. or laid up with two broken legs, you got up and attended. It was not questioned – it was done.

At the ‘aha, matters of importance to the entire family were discussed, and once a year plans for the Makahiki were made. Family members were reminded of teachings, when it was felt that one or a few needed to he reminded. One teaching that people needed to he reminded of most frequently was: To say that one forgives and then not forget, is not to forgive at all. Forgiving and forgetting are part of the same whole. To say you have forgiven and continue to bring up the problem is a great error and is to carry a large rock in your “bowl of light”. For the reason of forgiving and forgetting, many elders did not wish to discuss the past with the children. Starting to tell stories of long ago could often bring back old hurts, old feelings of resentment and anger. Stones long gone would arise again. Some who had moved on into the spirit world might be dishonored. So they felt it was best forgotten, and our history was buried with the kupuna and it was no more.

The ‘aha consisted of the flesh, or living family, and the spirit family. That a person had passed from flesh did not make them less family. They were spoken of and to, remembered in mele and chant. At meals they were remembered before the family ate the food. For this reason foreigners said we had hundreds of gods that we prayed to. Gods indeed, they were our family – our loved ones – our parents.

The ‘aumakua was also a part of our family circle, and explaining this is difficult. Perhaps you could understand it as a guardian angel. Christians believe that – well, we had our ‘aumakua. That is as near as I can explain it. The ‘aumakua was our identity and an important part of the family. It did not need to be in the body of anything, however, for the ‘aumakua was a spirit. They were like a messenger between the two worlds – the spirit and the flesh. They had access to both worlds (or places). Our family ‘aumakua was a Mo’o (lizard or dragon) my mother’s family line had as their ‘aumakua the thunder.

If we were one with all things and all matter, we were one with them and they were one with us. Why should that seem so strange? Our family ‘aumakua were sometimes printed in kapa design on our family banner for the Makahiki games. It was to bring forth all the mana of the spirit family. Nobody was afraid. It was all part of the fun.

Our rules or laws were few in the family but we all knew them by heart. All were free to come and go. and do as they wished, as long as they did no harm to another.

All that was worked upon was shared with the family. divided into four portions; the first going to the elderly who could no longer work for themselves. Who the elderly were, was not decided by any but the person himself. Some worked hard every day and were far older than some who had laid the day’s work aside. Each knew his own heart and body. They knew when they could no longer share in the work load.

We shared with other members of the family and took the last portion for our own household.

Our family did not consider ourselves to be ali’i. We considered ourselves to he above ali’i. We were a sacred line, here from the beginning of time.

Once a year. at Makahiki season, we had presentation of family. Every family member who was alive attended this meeting. Family members that had moved away from our community returned. It was a time of great rejoicing, remembering and romancing – for we met family we had not known before, and the young ones fell in love, some stayed behind when the family left, while others left with cousins when the time came to leave.

At the presentation of family, each family line was presented and the genealogy recited of that line. With our family, all the children of my grandfather Kaiakea, their wives and children, grandchildren and great grandchildren would all be in attendance. This was the only time we saw each other all year, as we all had families of our own and the rest of the year we were busy with working the land and caring for the things that filled our days and nights. At these great celebrations all the old chants were told; of our history, our heritage, of Moloka’i o Hina. There would be many tears and much laughter. All who had passed into spirit during the year would be remembered, and chants and mele in their honor recited.

During this time, we did no work except for the preparation of food and other essentials. The days were full of games and contests. When the best of each game or contest was decided, these were the participants who represented our family against other families in the islands. This was mainly in sports, but included games of skill and martial arts. When the time came for our family to participate in the games against other families, we stood as one body behind our players. We cheered and yelled. and on occasion, when we felt a member of the other side did not play honorably we called him names and reviled his ancestors (for which we all had to be penitent later). Then as now, people were people. We had good times and bad times; fun times and hard times. The difference comes when it comes to family. Then we were part of the whole. We had our ‘Ohana.

Hakahaka Leo O Ha’i ‘Ouli: Omen Readers, Seers and Prophets

Since the beginning of time there have been seers and prophets living in our islands.

Ali’i prophets were often part of a group that served the chiefs. Chiefs wanted a prophet close at hand at all times to consult in regard to wars, his health, his future in general and the future of his enemies. Some of these prophets only prophesied things the chief wanted to hear (would plant a thought), and the chief, hearing and wanting these things to happen, would act accordingly (‘upu).

The ali’i had other prophets – that would not lie, but told things as they really saw them. Some of these were put to death for being so truthful. The ancient ones (the pre-ali’i) had many men and women who had been born with the gift of prophecy. These people we saw as special. It was our belief that these people were very old souls who had come back into flesh to help others. Sometimes this was a family member (close family) or someone of a far branch of the extended family (ohana Iaha). We called these people kaula. It meant prophet. but it meant more than that – it meant pure energy – a true light carrier. Many of these prophets were also teachers. Around their schools (halau) and temples (heiau) they had many White Ti plants growing and Kukui trees. These were a sign to any who needed refuge, that this was a place safe from the storms of weather, or the storms of life.

Kaula were not people who would seek the limelight. You had to seek them out, if you had need of such a one. All were welcome at their door, ali’i and commoner alike.

Some of these holy ones asked questions, or requested certain things be brought from the forest or the sea to help him read the signs. Some had no need of anything except the question, and the truly great ones did not even need the question. Not all kaula found the answers the same way. Some shut their eyes and seemed lifeless. They would seem to not breathe. While in this state they said they could go to family in spirit, the future or the past to find the answer. Some said they would consult the family ‘aurnakua.

The sex of the kaula was of no importance. Their ability, energy, and force was all that mattered. My own kumu (teacher) Maka weliweli, was a great prophetess and seer. The greatest kaula in our family, however, had been Kiha Wahine of Hana, Maui. It was her name I was given as my sacred name at birth, because it was hoped that I had been blessed with her mana (ability-strength). Maka weliweli was to teach me the things a seer or sacred one should know.

On Moloka’i the term kaula was not often used, but then kahuna was seldom used either. Perhaps this was because we had some of the most outstanding prophets and seers of Hawai’i nei living on our island. Lanikaula of Puko’o was a great one, Kai-akea was perhaps just as great but in different areas, and his daughter, the famous Maka weliweli, were just a few.

When I was about 13 years old there was a memorable experience involving one of the elders of our family. I do not know the name of the prophet who was involved in this happening. but the incident has always remained fresh in my memory. My great-uncle had broken his hip and it would not heal. The bone doctor had worked on him but the bone would not stay in place. The elders sent prayers to our ancestors and all of us who loved him also prayed in our own way. Offerings were made at the family altar. The herb doctor gave him medicine so he would not be in pain but still he did not get well.

One morning my uncle asked that he be carried to the Kukui heiau in East ‘Ohi’a. It was an agricultural heiau, but uncle had heard they had a great healer there. It was quite a trip to carry an old man, but uncle was greatly loved, and his request was honored.

The elders chose four strong young men to carry Uncle Pu’u, and the elders followed behind. Food was carried for the journey. and mats so they could rest along the way. This healer was not of our family. and it was not known if he would see or help my uncle. Along the way the elders prayed. This whole procedure was most unusual. Family treated family. Everyone felt great suspense. Those of us who stayed behind tried not to worry but let the spirit family take care of uncle and the elders on their journey.

Uncle Pu’uolani had been one of the ruling elders of our Ohana for many years. He was very aged, but his mind was quick and his eyes bright. Before they started on the journey he asked the elders to pick another to sit at the ‘aha (council) for him until he recovered. Pe’elua (my father) was picked, so he had gone with the elders on the journey to the Kukui heiau. It was from him that I heard the story in detail when they returned.

The trip to the heiau had been without incident. No one had called to them, there had been no barking dogs, the skies had been blue and clear, a high arched rainbow walked ahead of them. As they approached the heiau, a man came toward them. It was a strong youth in his mid-twenties. He told the men that he knew who they were and why they had come. He told them they had brought uncle a long, long way for nothing for his hip had already begun to heal. Uncle was old but he would live a long time. Then he looked straight at Manu, my cousin, who had helped carry uncle and told him to get his house in order, for his time was near. There was no way this young man could have known who they were, or why they had come seeking aid. They asked if he was the one they sought (for they had expected a sage of great years). He smiled in answer and invited them into the heiau for rest and food.

They rested that night at the heiau, with the young man and others like him giving them food and seeing to their wants. The next day they began the return journey home. Now that uncle knew he would live, he was at peace and quite merry. He did not feel ready to walk to his ancestors.

When people died and did not wish to go. or died quickly as in battle or some accident, they sometimes stuck around in spirit doing mischief. It was for this reason that we wanted all of the Ohana to feel at peace when it was their time to go. The ‘aurnakua was waiting for them, would make the walk easy for them and make them welcome. It was the job of the family in flesh to help each other be at peace within ourselves, especially when we were about to leave this life and this body. When someone (as uncle had done) stubbornly refused to go, we did all we could to help them stay.

We were taught from the time we could understand, that there are no accidents. All things happen for a reason. We may not know what the reason is at the moment, but we were told to always be happy even for misfortune, for with it comes some wisdom that we could not have had otherwise.

In Uncle Pu’u’s case, he lived several more years. Uncle had some difficulty walking after that and used a stick or cane, but when he finally passed over, it was in his sleep, with a smile on his face.

My hanai mother and my cousins who lived with me at the halau felt perhaps Uncle Pu’u had to go through such pain so that Manu could know it was time for him to go. He was the young man who carried Uncle’s leg on the journey and whose death was foreseen.

No one spoke of what the healer had said about my cousin Manu, but no one forgot it. I expect it was heavy on his mind as well. He made many trips into the forest alone and to the heiau at night, when it is easier to speak to the gods, and the ancestors. Manu was still quite young. He and his wahine (woman / wife) had three small children, a newborn at the time, a little girl was just learning to walk, and a small boy of three years. Manu was a good man; a good fisherman, a good net maker, a good bird catcher and a good father. He was quick in his mind, and kind and thoughtful of others. He was already being considered to join the elders when he grew in years.

One day as he was throwing his net way out in the water, he saw his small son trying to come to him. He dropped his net and tried to get to his son to save him from drowning. His foot caught in a bit of coral and he fell under the water. He and his little son took the trip together to join our ancestors.

In our family, many things were known about each other. That was how we helped each other. In the case of Manu, his death had been foreseen by someone not of our family. That was most unusual. That is perhaps why it has always stayed with me. All people are our family, are they not?

My teacher and hanai mother Maka weliweli was great in knowing the future. She taught those of us at her halau so that we could know the future and the past. She taught us to leave our bodies and search out answers. These were lessons that took many, many years.

From the time I was quite small I realized there was something different where I was concerned. No one was allowed to touch my clothing. I knew I had a sacred name that had great mana (strength or power) but I did not know what it was. Sacred names were not told to us until the family elders decided the name was correct. This didn’t happen with some until they had been grown for many years. Sometimes the name was not told until the death of the one who gave it. Sacred names were just that – sacred, and not to be fooled with. Only one person alive could carry a particular sacred name at one time. To give a child a sacred name of one still in body was to welcome disaster to the child and to the parents. To name a child with the known name of another (one who was loved and honored) was done often. In this case something was added such as opio (junior) to show that this child had been named for the elder of the same name. We had many Kaili’s in our family – all with different endings. My sacred name was mine alone and I would not know it until the time was right.

The tradition of carrying the name of some one of your family line, now deceased, was done if the elders felt a certain person had returned to flesh. At other times, it was to bring the strength and wisdom of that family member back into flesh (almost a “wishing it so” type of thinking). In cases like that, it was not always right and names had to be changed; sometimes because the name was too heavy (powerful) for the child to carry, and it could be seen by the family that the wish would not be fulfilled. In some cases, Ka Maka o … would be used.”…the eyes of…”, adding the name of the one whose name they wished to use. This was a sly way to try to get around what the family in spirit wanted. In some eases they let it be. In other cases the wrath of the gods came down upon them and the name was hastily changed.

It would seem to a Christian that what a child’s name was would have little importance, and yet was not their carefully picking out names from the Bible book similar to what we did? Were these not holy names? Did they not wish to bring the mana of that person and their name to this new child?

My sacred name was not told to me, for fear I was not the right one or would disgrace the name, or bring discredit in some way. When I was told my name I was 12 years of age and had just become a woman. This was actually quite young to be told my sacred name.

My fellow students at our halau gathered kukui nuts, polished them carefully. and on the day that I was dedicated, gave to me my lovely kukui lei The nuts were uniform in size, polished brightly with the oil and fit around my neck perfectly. My kumu and hana’i mother, Maka weliweli, gave me a lei for my head made of kukui leaves and flowers. Now I, too, was considered a light carrier. My serious studies would now begin. I would learn the chants of our family. I had worked hard at my tasks these past years. I had tried to be humble; to listen and not to ask silly questions. I had tried to work quickly at the most menial task; to be prudent, patient, and always observing. I would now become a real student and be taught secrets I had waited long to hear. I was quite excited.

After my leis were presented to me, I was held by the hand and allowed to go up to the prayer platform where Maka weliweli sat to pray, to teach or to think. I sat facing my fellow students, and family members. Then Maka weliweli whispered my name to me and breathed into my mouth and onto the top of my head. To show emotion at this time was not correct. I thought I had not heard correctly. My mind seemed muddled and confused. The name she had given me was Kiha Wahine Lulu o na Moku (Sacred Woman – Keeper of the Islands). How could I bear up under such a powerful name? Tears were very close but from somewhere came a calm control, and the service of consecration continued without incident.

The known names in our’Ohana were crude and ugly. This was a common practice in the line of my father. Some of his sisters and brothers did not do that, but my father named all of his children names such as La hapa (half day – meaning shiftless or lazy), Ka’ili’me’eau (the itchy skin) and my name Kaili’ohe (the fetcher). but the saddest name was Ka mai wahine (the woman who was having her monthly period). The elders felt that mischievous spirits would not think we were worthy of their time and so would leave us alone. When I was older and lived among many foreigners I found their facial expressions priceless when we explained our names. You did not need to be a spirit to he turned away.

After the program of consecration took place at our halau a great feast was enjoyed by my fellow students, our families and our kumu. As important as this day was, the elders spoke of other things as we feasted that night. Things were changing in the world around us. Many foreigners had come to Hawai’i. Lahaina was lull of them and more were coming all the time. They had been able to push Liholiho (Kamehameha II) around, but the family understood that, for he was an even tempered man and not sharp-witted. He was also easily used by any who gave him liquor. Now there was a new king, Kaui ke a o uli (his younger brother Kamehameha Ill) who had been raised skillfully under the wing of Boki and Liliha. Kaui ke a o uli was a smart man. He had been taught to read and write by the long necks (missionaries), he carried the mana of his ancestors. Why then was he turning against his own people? Why was he taxing us so highly? Why was he sending men out as friends, to snoop and see how many pigs and dogs each household had – how many fishponds, how large a garden. One family member told us that he had heard that all the money being collected went into the pants of Gerritt Judd, and he would allow the king only money for certain things. They said in Lahaina they called Judd, “King Judd.”

The family was greatly troubled and talk went on until dawn. So it was, as I embarked upon my years of greater learning, the omens were already there, our world was changing around us. None of us spoke of the prophecy of Maka weliweli that they would run us over and stamp us out, but there were none among us who did not carry the thought.

When I looked back upon those days from later years, it was not difficult to understand. Our own teachings of love and light had made us vulnerable. We welcomed the foreigners with aloha. When they asked for this or that, we tried hard to make them happy. We did not know that men thought they could own things like land, or ocean rights. These things were for all to use. The ali’i parcelled off things for their own use, but with a new a/ti chief, these things changed. Our rights were curtailed only temporarily. The foreigners were not able to see or understand how we believed from their pathway on the mountain. We were not able to see how they thought and felt from ours.

We, on Molokai, believed in the light. We tried to keep our bowls full of pure energy and to light the paths of all who came our way. Our people had been taught by holy men who had come to our shore centuries earlier that there was an Enlightened One. They spoke of him as if the sun shone from his back, and the a/i’i had copied this in their “burning back kapu. When the missionaries came they showed us pictures of Jesus. He was surrounded by light. The stories they told us from their Bible Book were full of loving one another. So, we all became Christians. I became a Christian many times. I found that I was alsopa’a (locked into my past). I continued to go to the halau; to meditate and spend hours in meditation. I could see nothing wrong in trying to keep my bowl full of light. It was difficult for me to understand why the foreigners did not wish to see anything.

Ka Kahuna Kahua Haua: The Kahuna System

The word kahuna was not often used by us. To place it in front of a title denoted that a certain person was the highest expert in his field whether in the Ohana or on a specific island. The student who studied under such a one was not given this title even if he had studied for many years. It was not until an elderly kahuna was about to pass from life that he would designate who was to follow him. If a pupil was highly favored with wisdom and quickness of mind the kahuna would call him to his side, breathe into his mouth and pass on some bit of knowledge that had not been taught in the school. When the elder breathed his last, the new appointed one would pick up his duties. He who excelled all others became the keeper of the secret.

The term kahuna was not as revered by us, as it was later. It was any person with great knowledge in one or more fields. There were over 40 kinds of craft kahuna alone. There were 14 kahuna of the healing arts. There were also counselors to the chiefs – those who were the politicians. Since all the elders in the family were expert in many things, we were more inclined to think of them as grandparents, aunties or uncles.

The men who made canoes were considered by most people to be the ones with the highest mana (power) – that is to say, the greatest skill. Canoe making was learned only by a few to the point where they were considered kahuna. Craft people in mat weaving, coconut weaving, fishnet making, spear-making, kapa dyeing, kapa beating – were all considered kahuna when they became expert and could do things in their craft beyond the normal expertise of men.

The things we made were the fundamentals of life. We all learned to do many of these things. In those days we had no stores. What we needed, we made.

The word kahuna began to be misused in the mid-1800s by foreigners who did not understand Hawaiian terminology. By 1900 the word brought fear to many. There are always people who wish to trade on the ignorance of others, and these people found a good market among the foreigners. There were Hawaiian people who sold herbs as love potions and who used other herbs and prayers to end problems, or to bring pain or sorrow to an enemy.

In the islands at that time, there were many foreigners. On O’ahu and Maui they rushed to get potions with one hand, while they held their Bible in the other. It made the elders of our family shake their heads for those of our family who participated in such dealings. They made money, for they were well paid for their herbal potions. What power they had was lost – for they had lost the light from their bowls for the sake of fun and profit.

There were other kahuna. These were the priests that lived at the heiau (temple), the ones with the great power to tell the future, raise the dead, touch you and heal you. These people were called seers or kaula. They lived alone, or with students, and were only seen when someone searched them out. Today they would be called priests. They took no money for what they did. Still today, the test of a person being full of light is – do they charge a fee? If they do, beware. Those who carry the light help all people who ask for assistance. They, in turn, will be assisted by another when it is needed. Although it was customary to take food to be offered to the gods when going to the heiau (temple), it was not necessary to take a gift to the priest. They had farms and fished, just as we did. The students took care of the chores, and learned humility. Part of their training was to know all parts of life.

There were other kinds of kahuna who came with the ali’i. These were the men who plotted wars, had men killed as sacrifices at their heiau (temple), and caused great destruction among our people. The first of these was Pa’ao who came around 1250 AD. These men were not of our people, and we had to keep them from the shores of Moloka’i. There were times, when in order to protect our island from the forces of darkness, our people banded together and used all of our knowledge to keep those who would destroy us from our shores. It was at this time that Moloka’i began to be feared, for it was seen by many as a place of great power, and that it was.

In our ‘Ohana all who kept the rules of the family had great power. When rain was needed – rain came. When there was enough it stopped. That was child’s play and only needed good concentration.

Children in training in weather reading or star reading spent hours in contests of will, each concentrating against the other to make a cloud larger or smaller, to make it rain or clear up. Conditions would sometimes alter all day long as the children seesawed back and forth in their contests of will.

There were other contests of concentration: moving objects – sending them away. or finding them and bringing them forth. Stories of such things are now considered untrue. When I was growing up, it was everyday practice.

Life was a school. Life is still a school. People continue to learn as long as they live. The Hawaiian way was to believe that we had been born to learn, and we would continue to learn as long as we walked the earth. We had never heard of marching off to a building with a rice ball and a piece of fish for a foreigner to teach us about life. Our teachers were members of our own family. Who could better know our needs? The elders of our family were wise. By watching the children and seeing what they did well and what interested them, they helped us to place them with an uncle or auntie who could teach them all that there was to he known about a particular area of knowledge. Many children were placed at birth, or by the time they were one or two years of age, because they had already shown the path upon which their heart would lead them.

These children, because of signs at their birth, were given to someone to raise and teach in a certain craft or art. This placement was no more wrong than the placement of children when they were older. The kupuna (elders) knew what they were doing. Children placed at birth were usually the ones who were to be schooled as readers of signs and omens, navigators, or practitioners of the healing arts. Children chosen latest in life were the ones taught the history chants of the family. These children were usually being taught something else, and when their ability was seen, family chants were added. The history of the family was of great importance. The child had to show a good memory, love of detail and be able to sit for long periods of time in deep concentration.

In our family, after a near disaster when the young man who was learning to become the genealogy chanter died, the elders chose two replacements – one boy and one girl – to be trained. Thereafter, this was the custom. This happened long before I was born, but, because of it, my family knew the stories of its past, and I have the stories to pass on to my children.

Children who would study the genealogy chants were made known at a ‘aha’aina ho’olilo. The elders observed children under consideration for some time. When a sign was made known to one of the elders it was shared with the others. The sign was discussed and, if all felt it was right, it was time for the ‘aha’aina ho’olilo. At this time the family gathered together. The chosen child or children were presented and taken to the heiau where a ritual of consecration was performed. During this ritual the one who was the teacher would breathe into the child’s mouth, and onto the top of the head and say, “May this mana, the gift of the ku’auhau’aumakua pass through me, and guide you. Thus the child’s years of training began.

Up until 1840 all children of Moloka’i started their years of training with a ritual of consecration at the heiau. More and more, thereafter, this ceremony was carried on between the teacher and the child at the place where the teacher lived. This was due to the growing feeling among the people that to go to the heiau was to bring shame to themselves if discovered. By the turn of the century going to the heiau – by any except the very old – diminished. The young wanted to do things the ha’ole way. Many parents felt shamed by their children, so they discontinued old ways. It was not so much the missionaries that changed things on Moloka’i as the younger generations.

Many of the people from Moloka’i moved or took trips to other islands, to Lahaina and Honolulu. They felt Moloka’i ways were backward. They laughed at their family’s beliefs and way of life. Many of them refused to take part in family ceremonies, especially ones held at the heiau. The leaders had lost their place of wisdom in their eyes. The young looked up to no one. For this reason I tried to keep my family from going to the city. I felt evil came in the cities, and had seen no good come from them.

My people – those who were living here long before the arrival of the ali’i- had several kinds of heiau. We had fishing heiau – for good fishing and for the care of those of us who fished the ocean. We had agriculture heiau for good crops and the care of those who farmed the land. Each school had its own heiau where the students asked their ‘aumakua for special care and assistance with their lessons. There were also heiau for Ku or Hina – our parent earth, sky and sea. Before the ali’i arrived we had no wooden statues in or near our heiau. Later, under their influence, most of the heiau on other islands had tiki. On Moloka’i this was done at Halawa by Kahekili and other chiefs put tiki gods at other sites on Moloka’i. Our heiau remained as they had throughout generations before us. Our people, the pre-ali’i, used the upright stone to designate the Father of all, Ku – and the prostrate stone to designate the Mother of all, Hina.

When anyone in our family found a stone that was long and smooth we would wrap it in a ti leaf and take it to some sacred place or to the family worship center. It was always considered a good sign to find such a stone. The rock had life just as we did. We felt it made the stone happy to be in a sacred place. I still think so.

We did not think of the heiau or the people living there as having supernatural power. We were taught that all things were natural. We were one with all of life – each particle of sand – each drop of water. All was a part of the whole.

All things were counted by four – probably because we had four fingers on each hand. When we took gifts to the heiau to put on the lele stand they were in quantities of four. One was for the earth from which the food grew, one was for the life-giving force, one was for the cleansing ocean and one for the purifying force of fire. It has often been said that girls did not go to the heiau. Under the ali’i rule I cannot really say, but in our family and at our school we had a heiau and it was very much part of everyone’s life. I had always been very interested in my spirit family, so I prayed to them, made offerings to them in thanksgiving for my blessing, and no one ever hindered me.

When I was old, my grandchildren and great-grandchildren informed me that girls did not pray, only the men in the family prayed; that the men had the right to put women to death for entering the men’s eating house or any heiau. It might have been an ali’i rule but when the ali’i lived among us they did as we did. My grandfather Kai-akea had the reputation of disregarding any and all ali’i rules he did not agree with.

The practices of healing were much the same in all of Hawaii nei. The family ‘aumakua was asked to help bring about good health. Those in the family who were in the healing arts worked with any person who was ill. They would talk to the patient at great length about any stones they might he carrying. They would pray that all stones be dropped from the patient’s bowl of light, and if anyone in the spirit world had ever been offended by the patient, that the person in the spirit world would now forgive the one who suffered.

There were times that patients were told that their illness was part of their learning process. This was to help them learn some lesson that they had, up to now, refused to learn. The lesson may have been of humility. When such a thing happened the family accepted it and helped in any way it could.

I prayed to Ku and Hina because they were our first parents, looked out for us and cared for us. I in turn loved them. I did not ask them to help me with my problems. If I had troubles, or there was a familv illness or death I would go to my teacher and hanai mother, Maka weliweli. Sometimes I was told what was wrong before I was able to make a statement of what my problem was.

There were times when finding a solution to a problem was not easy. Trouble was sometimes caused by someone outside of the family circle. If the elders thought this was the case they had us all wear ti leaf leis. called la’i lei. If this happened we all recited that the ill return to the place of its origin. “May the one who sent the problem or illness accept it back and free us from its grip”.

If for any reason one of the great healers was sent for to offer aid, it was important that all signs be good. It was always best to not arrive before his meal for then he might not come. If he did come and someone called to him from the rear he might turn without finishing his journey or seeing the patient. Now it would be called bad manners but then it was seen as a bad omen. At such times when prayers were offered, they were sent to everyone. We sent them to the Christian God after He came, to the ali’i gods. and to the family ‘aumakua and all of our ancestors. At such times a feast was prepared and presented to the ‘aumakua. We prayed 0 ke aka ka’oukou, ‘o ka’i’o ka makou, which means, yours the essence, ours the flesh. They got the smell, we got the food. Then the leftovers were burned, but the leftovers were usually few. Later I learned that the Chinese do this when a family member dies, and at other certain times of year. It is a small world.

Our family had a special ‘aumakua. It was called Mo’o Kiko and lived near the heiau in Kapualei. It was a giant lizard we were told and when I was small I had dreams of him. I did not ever see him. I felt no fear for if he was a part of our family there was no need to fear. Some said the Mo’o was Maka weliweli, and that she was a Mo’o I have no doubt, but I heard the story when she was alive. When I became old, there were those who called me Mo’o Kiko. I am sure they did not mean it as nice, but to me it was not an insult. I would smile. There is so much for us to learn. We are all so far from the top of the mountain.

Manawa Mau Loa Aku: Eternal Time

In the early days. that is, before the Tahitian ali’i came to these shores, our powers were great. Our koa bowls were full of light and we could do all things. There were no laws of life or death in those days. That form of rule came with the ali’i. Our only law, if you want to call it that, was that all are one. Anything said to hurt another would hurt you also. You cannot strike your brother without it also striking your parents and your ‘aumakua, so it was best to strike no one.

In those days, it was commonplace for people to lie down, and their mind go elsewhere to check out weather conditions, to see a loved one far away, to fly with the birds – or to find the answer to a problem too hard for the mind in body. This is still carried on to some degree, but far less. Now it is usually done only by a few, who have kept the light.

In those days. and after the ali’i came too, we could think people home. We sent messages to them wherever they might be and have them come home if we needed them. They always got the message and came home. The ‘aumakua would protect them. We would keep them in our mind, always safe, always well. We didn’t worry. We knew they were cared for. The ‘aumakua could do many things for us like that, that we could not do for ourselves. It was a good arrangement, having part of the family here in school, the other part watching over us, and guiding us.

Our time was not of a clock. It was of the day, and of the night, cycles of the moon and the time of certain stars in the morning or evening. We had divisions of time, but nothing as rigid as a clock. Yesterday, today and tomorrow were one. We had been here before, we would be here again. We were here for a reason – to learn. Sometimes we had to come back many times to learn the lessons being taught. Sometimes we learned fast and could continue our journey on the other side, and guard and watch over the family in body.

There were many lessons to learn. One that seemed hardest for all to learn was that force of mind and force of the fist are never in the same body. The energy will go to only one.

It took time for me, as a child, to understand that the people who gathered at an ‘aha aina or ‘aha were only half of the family. The more important part, our ancestors, shared these meetings with us, listened to our problems and did what they could to assist us with our difficulties. Help was given to us in many ways. Our spirit family – who knew the way of the light so well, and knew the power and the problem of the stones – they blessed us, surrounded us with light, their love, and gave us dreams to help us understand and to learn, watched us fall on our faces, helped us up. and started us on the pathway of light again, and again, and again.

Everyone in the ‘Ohana had a high degree of dream understanding. From the time a child began to talk, his dreams were discussed with him. He was shown through his dreams errors, and how to correct them. He learned of things past and things future, of body conditions that needed correcting, and warning signals of illness. Some dreams gave clues as to what a child would become when he became an adult, and names of all children came from dreams. No child was ever named without the spirit family being part of the naming process. The parent, a grandparent or an elder of the family would have a dream, and the child was known, and his name given.

We were taught four different dream levels. One was the physical – pertaining to all aspects of the physical body. The second related to members of the ‘Ohana and help needed, or warnings. Third were the mental dreams. In these, learning took place. Schooling begun during waking hours often continued in these dreams. The fourth level was the spirit dreams. On this level people leave the body during sleep and travel, in those who were advanced in dreams of this sort, they walked to the other side of the rainbow and talked with their spirit family if there was need of it.

The Hawaiian people have always believed in many lives – in a continuing river of life. A life that flowed in and out of the earth plane, learning something new each time, always moving forward. Never being put back for mistakes, but given a time to think things through and then continuing on, correcting errors and making new beginnings. There was no word for “sin”. We had to invent one after we were told we were sinful.

This was a great difference between the Hawaiian beliefs and the beliefs of the foreign people who came to teach the Bible. They believed there was no river, no flow to life. It was a once or never trip. They meant well. They tried hard. They spoke love, they taught love, but they didn’t know love. They taught “thou shall not” – and they were angry with us all the time for having fun and for the laughter and joy in our lives. They were not allowed joy. Salvation came to them only through misery. The Hawaiian gods were far more kind, for they loved happiness and joy as much as they loved sun and rain. They loved bodies the way they were made, glistening with sweat or with water from the ocean. They saw what we were, and it was good. The foreign God wanted every man, woman and child covered up and hid from themselves and each other. He was ashamed of his children. This is what the missionaries believed. I am not sure they were always right.

Jesus was a lover. He taught love. All the stories they told about Him were about love. He taught the same things we taught our children – don’t kick unless you expect to be kicked back. Don’t say mean things, for words hurt worse than stones. Love the old ones, love your parents, love your sisters and brothers. Love the babies. The more love you give, the more you will receive back into your life.

The missionaries didn’t always listen to the things Jesus said. The rules they made and lived by did not come from Jesus. They did not come from the Bible. The rules came from their own minds and hearts. They worked very hard at being Christians. It was a religion of laws and rules more strict than our own kanawai (laws) had been. I am sure their God loved them for all the misery they endured.

I too loved Jesus so I let the Hitchcocks dunk me and I became one of “their flock”. I helped build the church at Kalua’aha. I tried to live like they wanted me to live. Many times I could not understand but they were older than I, they were the teachers – I was the student. I respected them. I covered my body. I did not drink of the ‘awa root. I didn’t play in the surf on Sabbath but sat listening to sermons all day. I gave up many things that to me were pleasurable. I did not understand many of their laws, but I kept my questions to myself. Only once I asked a question. I wanted to know about the wives of Jesus – how many he had, what happened to them and how many children he had. Everyone was shocked. They said He had no wives at all. He was pure.

Pure is full of energy – not being full of stones. I did not see what that had to do with how many wives he had. Who cared for this man? Who went with him on his journeys and prepared his food? Who put his mats down for him at the end of a long day and massaged his tired muscles? Was this, then, the job of the disciples?

When Father Damien came riding along on his donkey and wanted to talk to us. we were happy to see him. We fed him and gave him a place to rest. I told him I already knew about Jesus and loved him very much. That made him very happy. The next time he came, he sprinkled people and blessed them and I had him sprinkle and bless me. It was a wonderful day. We were all very happy. Father Damien wanted to build a hale pule (a house of prayer). We promised to help him build such a house. We had houses for our gods, so we agreed he should have a house for his god too.

Father Damien was a quiet man who never yelled at us, or seemed to get angry at us. He asked us questions about why we believed certain things. We loved him. We all wanted him to stay with us, but he always got on his donkey and rode away. He explained that Jesus never had a home or a bed, and, like Jesus, he would travel from place to place telling people about the love our heavenly father had for us. Watching him I learned about Jesus. They both were alone. No one took care of them. They had no ‘Ohana.

One day the teachers at the school and church at Kalua’aha heard that Father Damien had been coming to visit us, and that we were building a hale pule for him. Several of our family who had been “sprinkled” were summoned to Kalua’aha at once. The fathers and mothers at the Mission Station were very angry with us. They said he was not of love, but of darkness. They said his long coat covered a tail, and his hat covered horns. We were all very shocked. We walked home slowly talking about this problem. Maka weliweli had taught me truth was always the same – yesterday, today and tomorrow. What had been truth hundreds of years ago would still be true hundreds of years in the future. Now, I was being told things that confused me. They all carried the Bible Book. They all told stories of God’s love and Jesus. They all believed in prayer houses and meeting on the Sabbath and keeping the day holy, Yet – one now said the other was not of light, but of darkness. By the time we reached home our decision was made. When Father Damien came, we would just lift up the dress (coat) and check his bottom. We would remove his hat and look for horns. If there was no tail, if there were no horns, we would know that he was of the light and we would continue to build for him his hale pule.

When Father Damien came the next time, there was great excitement, for even the youngest children had heard, and were anxious to see what was beneath the robe he wore. Before we had a chance to explain to him what had happened, the children rushed forward and pulled up his robe and thoroughly checked out his buttocks. They were nice and firm, and quite normal. We were all satisfied. The stone belonged to those who would have us believe in such nonsense, and the matter was closed. Father Damien had a congregation.

The matter of the time was one that was never resolved between us and the priests of either the Catholic or Protestant faith. To them everything was so very urgent. They were always in a hurry. I often wondered why they did not take time to enjoy anything along the way. We continued to do things when the omens were correct, and wait when they were not. It would be foolish to carry rocks from a certain beach to build a church, then have a big rain come and wash them all back to the beach again. When the rocks wanted to be a part of that church, when the sky and sea and surf were in accord that these were the rocks (or coral or ohia logs) to go toward the building of something, we would know. In the meantime, we had our daily chores to do.

To the Hawaiian heart there was the Ao (day) in which we did all manner of toil, for ourselves, our family, our neighbor, our old and our young. When the day ended, so did all work. No nail was pounded, no floor was swept, no hair cut, no dishes washed. With the setting of the sun, all work was finished until it rose again. Po (night) was spent in rest, visiting, remembering days of old, story telling; chanting and singing; in sharing time with our spirit family and in setting things straight around our own family circle. It was a time for joy and a time for love. It was the part of time that would ever be eternal.

Huliau: Time of Change

I might not have known which people were my blood parents, or cared, had circumstances not willed that all should be known. I was not raised by my blood mother, and children belonged to all of the family, not just one set of parents.