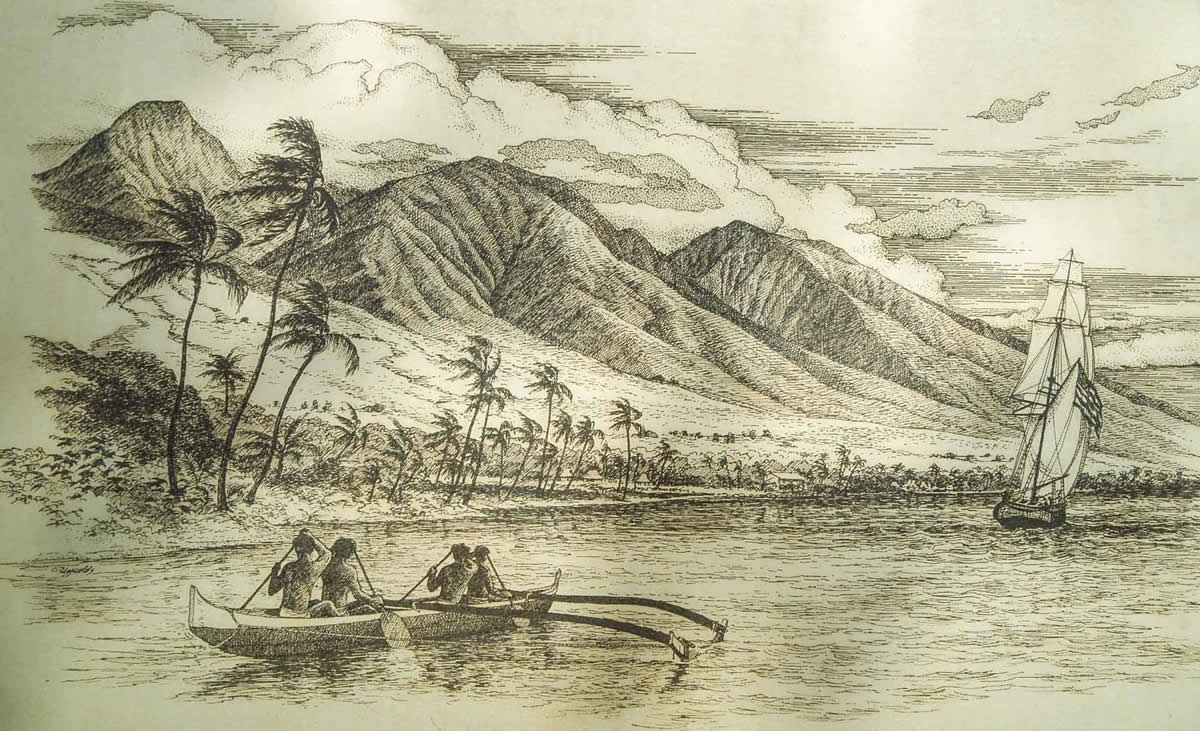

The Gustavus III

By John Bartlett

John Bartlett was a seaman aboard the Gustavus III, an English fur-trading vessel that put into Hawaii in 1791.

August 23, 1791

All the next day we lay with the main topsail to the mast and the courses held up, trading with the natives off Kealakekua Bay. We bought a great number of hogs, potatoes, breadfruit, grass lines, and kapa, which they make from the bark of trees and use for their clothing. It looks very much like calico but will not stand the water.

We had upward of one hundred girls on board at a time, but not a man excepting one at a time. One of their chiefs came alongside with one of young Metcalfe’s muskets. He was one of the stoutest men that I ever saw. Our captain compared his hindquarters, to that of a bullock and would not suffer him to come aboard.

Afterward the captain asked him for his musket and made signs for him to stand on the quarter bridge of our vessel, and when he did so the captain gave him his musket and at the same time fired a musket over his head, which made him jump overboard and swim ashore. At night every man took his girl and the rest jumped overboard to swim upward of three miles for the shore.

Early on the morning of August 25, we took our departure from the island of Hawaii, which is a very fine island with level land as far as we could see to the windward and with mountains on the lee shore with snow on them all the year round.

At 10 A.M. saw the island of Maui. A great number of natives followed us from the island of Hawaii. At six o’clock the next morning we saw the island of Oahu and at 10 A.M. came to, in twenty fathoms of water.

A great many natives came alongside with plenty of hogs, potatoes, yams, breadfruit, grass lines, spears, mats, mother-of-pearl beads, and a great number of curiosities. All hands were employed the next day in buying hogs and vegetables for a sea stock. During the morning the natives stole the buoy from our anchor and kept stealing and cutting all the hooks and thimbles they could get at.

The next day, Sunday, August 28, the king, his brother, and son came on board and made the captain a present of three red feather caps and some kapa cloth. Our captain gave them a musket and some powder. This day they sent all the handsomest girls they had on board and gave everyone their charge how to behave that night. When they gave the signal every one of them was to cling fast to the Europeans and to divert them while they cut our cable.

At night every man in the ship took a girl and sent the remainder ashore. At 12 o’clock at night the watch perceived the ship adrift and at the same time every girl in the ship clung fast to her man in a very loving manner. All hands were called immediately. I had much to do to get clear of my loving mistress. The girls all tried to make their escape but were prevented by driving them all into the cabin.

We found the cable cut about two fathoms from the hawsehole and made sail and stood off and on in the bay all night, and the next morning ran in and came to with the best bower. Saw a number of canoes trying to weigh our anchor. Three of the girls jumped overboard and two canoes came and picked them up. We fired a musket at one of them and a native turned up his backsides at us. We fired three or four more times, so they were glad to leave off and make for the shore.

The following morning a double war canoe came off with the men singing their war song. They paddled round our vessel and when abreast of the lee bow, seeing no anchor, they gave a shout and went on shore again. At eight o’clock forty or fifty canoes came off to trade but seemed shy of us.

We bought some hogs and potatoes and sent several messages on shore to the king, but could not get our anchor from him. At twelve meridian the king sent a man off to dive for the anchor, pretending they had not stolen it. The boat was manned and two bars put in her as a reward for the native if he found the anchor.

He dived several times but did not go to the bottom. He would stay under water longer than any man we ever saw. We could see him lie with his back against the bottom of the canoe for some minutes and then let himself sink down and come up again about three or four yards from the canoe, pretending that he had been to the bottom.

Seeing this, we were fully convinced that they had our anchor ashore and meant to keep it, so we sent another message to the king and told him if he didn’t send the anchor aboard that we should be obliged to fire on his town and lay it in ashes.

The next day we could not get a canoe to come alongside and could see natives running in from all parts of the island to assist the king if we attempted to land, which our mate was for doing, but our captain didn’t approve of it and so at eleven o’clock we got under way and fired four or five broadsides into the village.

We could see thousands of the natives running, one on top of the other. On the beach were a number of canoes off the lee bow, so we made for them and fired a broadside that stove a great many of them and sent the natives swimming and diving under water. We ran by two men swimming and shot one of them through the shoulder and killed him.

We also ran alongside of a canoe with a man in her. We stood by with ropes to heave to him to get him on board, at the same time pointing six muskets at him if he refused to take hold of the rope. He laid hold of it and hauled himself aboard and let his canoe go adrift. We then hove about and came abreast of the village a second time, when the natives on the beach fired a musket and kept running along with white flags flying in defiance for us to land.

Seeing no possibility of our getting our anchor we bore away and ran out to about two miles from the shore, where we gave the native on board six spikes and let him go to swim ashore. The seven girls on board we gave a number of beads and let them go likewise.