A Missionary’s Diary

By Laura Fish Judd

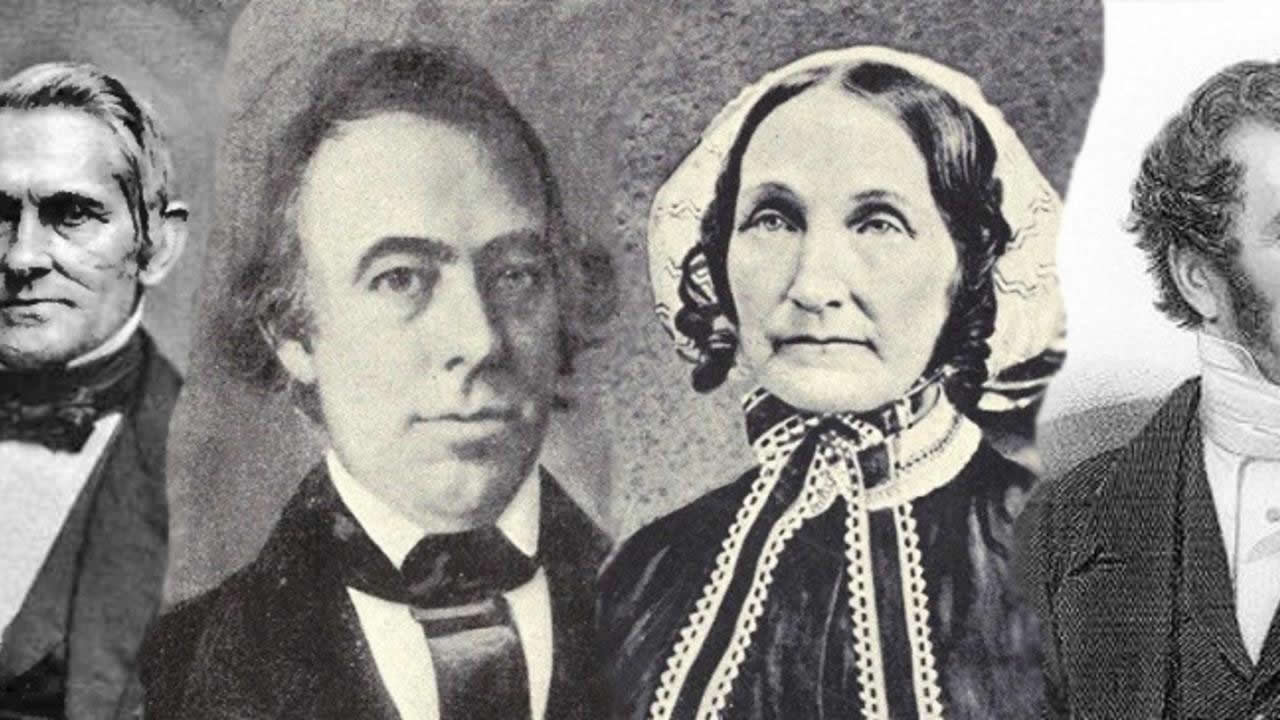

Laura Fish Judd, with her husband, Dr. Gerrit P. Judd, was in the “third wave” of missionaries to arrive in Hawaii.

Ship Parthian, March,1828.

Right before us, up in the clouds, and apparently distant but a stone’s throw, appears a spot of beautiful, deep blue, intermingled with dazzling white. It is land! – the snow-capped summit of Mauna Kea, on the island of Hawaii. Among the passengers the excitement is intense and variously expressed; some rush below to their staterooms to pour out their hearts in gratitude and thanksgiving, others fear to turn away lest the scene fade or prove a delusion, like our dreams of homeland; some exhaust their vocabulary in exclamations of delight; others sit alone in tears and silence.

What wonder that we so long for release from this little prison house! We have suffered many hardships, often unexpected. The ladies, ten in number, have been obliged to perform the drudgery of steward and cabin boy, as the services of these functionaries have been denied us by the captain, although, mirabile dictu, he did in his condescension allow his black cook to prepare our food after his, if furnished and conveyed to the ships galley. We possessed but little practical knowledge of the arts of the cuisine at first, but have sometimes astonished each other and ourselves at our success in producing palatable dishes, and most of all, light bread. These trials of patience and skill will be of use to us in our future housekeeping.

The voyage is now over, but I must run on deck to look again on that deep blue spot. The ship glides along smoothly; the clouds open – the blue space has become a broad mountain; now we see the green valleys and clashing cascades all along the northern shores of the island. The scene reminds one of the pilgrim’s land of Beulah. Can anything so fair be defiled by idol worship and deeds of cruelty?

We shall pass the island of Maui tonight, and reach Oahu tomorrow, which will be Sunday. We have packed our baggage in the smallest possible compass, and have everything ready to go ashore on Monday morning. We retire to rest with mingled anticipations of pain and pleasure. For once we regret that tomorrow will be the Sabbath; we look up for guidance – our Heavenly Father will pity us.

Sunday morning, March 30. The island of Oahu, our Ultima Thule, looms up in the distance, displaying gray and red rocky hills, unrelieved by a single shade of green, forbidding enough in aspect. Now we pass the old crater, Diamond Head, and we can see a line of coconut trees stretching gracefully along the sea beach for a mile or more. “Please give me the glass for a moment. There! I see the town of Honolulu, a mass of brown huts, looking precisely like so many haystacks in the country; not one white cottage, no church spire, not a garden nor a tree to be seen save the grove of coconuts. The background of green hills and mountains is picturesque. A host of living, moving beings are coming out of that long, brown building; it must be Mr. Bingham’s congregation just dismissed from morning service; they pour out like bees from a hive. I can see their draperies of brown, black, white, pink and yellow native tapa.”

Hark! There goes a gun for the pilot; our captain seems somewhat flurried: afraid of the land, perhaps; I surely am not. How I long for a run on those green bills! But patience till tomorrow.

Evening – our last one on board the Parthan. We have sung our last evening hymn together. Mutual suffering has created mutual sympathy, and we separate in Christian friendship.

We received a short but welcome visit from Messrs. Bingham, Chamberlain and Goodrich, on their way to hold service on board the ship Enterprise. They look careworn and feeble; Mr. W—- said “hungry.” They gave us a cordial welcome to their fields of labor,which they describe as “whitening for the harvest.” Mr. Goodrich brought some sugar cane and fresh lavender; the fragrance of the latter made me wild with delight. I have been on deck to look at the town and harbor. There are flitting lights among the shipping, but none visible on shore. The houses are windowless, looking dark and dreary as possible. Here we are to live and labor,” said good Dr. Worcester, “until the land is filled with churches, schoolhouses, fruitful fields, and pleasant dwellings ” When will it be?

Mission House, March 31. We passed a sleepless night; the vessel, being at anchor we missed the accustomed rocking.

At nine o’clock this morning we were handed over the ship’s side (by our kind and unwearying friend Mr. S—-, the mate), into the launch, and were towed ashore, twenty in number, passing quite a fleet of ships, on board of which we saw native men and women.

Landing at the fort we were received by the acting governor, Manuia, a very gentlemanly-looking person, dressed in half military costume. He spoke a little English as he escorted us to the gate, where vehicles were ready to take us to the Mission, a mile distant. These vehicles consisted of a yellow one-horse wagon and two blue handcarts, all drawn by natives, and kindly furnished by the queen regent, Kaahumanu; but I could not be persuaded to ride in such style, and begged to walk with my husband.

We stopped on the way at the door of the royal lady, who joined our procession after welcoming us most cordially to her dominions. She is tall, stately, and dignified; often overbearing in her manner, but with a countenance beaming with love whenever she addresses her teachers. She was dressed in striped satin, blue and pink, with a white muslin shawl and Leghorn bonnet, the latter worn doubtless in compliment to us, as the common headdress is a wreath of feathers or flowers.

We were followed all the way from the landing by a crowd of natives, men, women, and children, dressed and undressed. Many of them wore a sheet of native cloth, tied on one shoulder, not unlike the Roman toga; one had a shirt minus pantaloons, another had a pair of pantaloons minus a shirt; while a large number were destitute of either. One man looked very grand with an umbrella and shoes, the only foreign articles he could command. The women were clad in native costume, the pa-u, which consists of folds of native cloth about the hips, leaving the shoulders and waist quite exposed; a small number donned in addition a very feminine garment made of unbleached cotton, drawn close around the neck, which was quite becoming. Their hair was uncombed and their faces unwashed, but all of them were good-natured. Our appearance furnished them much amusement; they laughed and jabbered, ran on in advance, and turned back to peer into our faces. I laughed and cried too, and hid my face for very shame.

We reached the Mission House at last and were ushered into Mr. Bingham’s parlor, the walls of which were naked clapboards, except one side newly plastered with lime, made by burning coral stone from the reef. After being presented and welcomed, Mr. Bingham took his hymnbook and selected the hymn commencing: “Kindred in Christ, for His dear sake”.

Some of the company had sufficient self-control to join in the singing, but I was choking; I had made great efforts all the morning to be calm, and to control an overflowing heart, but when we knelt around that family altar, I could no longer subdue my feelings.

A sumptuous dinner, consisting of fish, fowl, sweet potatoes, taro, cucumbers, bananas, watermelons, and sweet water from a mountain spring had thoughtfully been provided by the good queen. As we had not tasted fruit or vegetables for months, it was difficult to satisfy thoroughly salted appetites with fresh food.

Kaahumanu treated us like pet children, examined our eyes and hair, felt of our arms, criticized our dress, remarking the difference between our fashions and those of the pioneer ladies, who still wear short waists and tight sleeves, instead of the present long waists, full skirts, and leg-of-mutton sleeves. She says that one of our number must belong exclusively to her, and instruct her women in all domestic matters so that she can live as we do. As the choice is likely to fall on me, I am well pleased, for I have taken a great fancy to the old lady.

After dinner she reclined on a sofa and received various presents sent by friends in Boston. Mr. Bingham read letters from Messrs. Stewart, Loomis, and Ellis to her. She listened attentively, her tears flowed freely, and she could only articulate the native expression “aloha ino” (love intense). At four o’clock she said she was tired, and must go home; accordingly her retinue were summoned, some twenty in number, one bearing the kahili (a large feather fly brush and badge of rank), another an umbrella, still another her spittoon, etc., etc. She took each of us by the hand, and kissed each one in the Hawaiian style, by placing her nose against our cheeks and giving a sniff, as one would inhale the fragrance of flowers. After repeating various expressions of affectionate welcome and pleasure at the arrival of so many fresh laborers, she seated her immense stateliness in her carriage, which is a light handcart, painted turquoise blue, spread with fine mats and several beautiful damask- and velvet-covered cushions. It was drawn by half a dozen stout men, who grasped the rope in pairs, and marched off as if proud of the royal burden. The old lady rides backward, with her feet hanging down behind the cart, which is certainly a safe, if not convenient, mode of traveling. As she moved away, waving her hand and smiling, Mrs. Bingham remarked, “We love her very much, although the time is fresh in our memories when she was very unlovely; if she deigned to extend her little finger to us, it was esteemed a mark of distinguished consideration.” She was naturally haughty, and was then utterly regardless of the life and happiness of her subjects. What has wrought this great change in her disposition and manner? Let those who deny the efficacy of divine grace explain it, if they can.

Crowds of curious but good-natured people have thronged the premises the whole day; every door and pane of glass has been occupied with peering eyes, to get a glimpse of the strangers. I have shaken hands with hundreds, and exchanged aloha with many more. We seem to be regarded as but little lower than the angels, and the implicit confidence of these people in our goodness is almost painful.

The chiefs of both sexes are fine looking, and move about with the easy grace of conscious superiority. Three or four of them, to whom we have been introduced today, visited England in the suite of King Liholiho, and were presented at the Court of St. James. They dress well, in fine broadcloths and elegant silks, procured in exchange for sandalwood, which is taken to China and sold at an immense profit; fortunes have been made by certain merchants in this traffic (honorable, of course, especially when the hand or foot was used on the scales !). Our captain told us that some of the chiefs had paid eight hundred and a thousand dollars for mirrors not worth fifty.

March 31. Nine o’clock in the evening. Is it enchantment? Can it be a reality that I am on dear mother earth again? A clean, snug little chamber all to ourselves! I can go to the door, and by the light of the moon see the brown village and the distant, dark-green hilIs and valleys. Strange sounds meet the ear. The ocean’s roar is exchanged for the lowing of cattle on the neighboring plains; the braying of donkeys, and the bleating of goats, and even the barking of dogs are music to me.

April 1, 1828. Mrs. Bingham, who is in feeble health, allowed me the privilege of superintending the breakfast this morning, as I am eager to be useful in some way. I arose quite early, and hastened to the kitchen. Judge of my dismay on entering to find a tall, stalwart native man, clad much in the style of John the Baptist in the wilderness, seated before the fire, frying taro. He was covered from head to foot with the unmentionable cutaneous malady common to filth and negligence. I stood aghast, in doubt whether to retire or stand my ground like a brave woman, and was ready to cry with annoyance and vexation. The cook’s wife was present, and her keener perceptions read my face; she ordered him out to make his toilet in foreign attire. I suppose travelers in southern Italy become accustomed to this statuesque style, but I am verdant enough to be shocked, and shall use all my influence to increase the sales and use of American cottons.

April 2, 1828. This is my twenty-fourth birthday. Have received our baggage from the ship. Found time to take a stroll with my husband, and on our way visited the grass church, where Mr. Bingham preaches to an audience of two thousand. The building is sadly dilapidated, the goats and cattle having browsed off the thatching, as high as they could reach. The strong trade wind always blowing sweeps through, tossing up the mats, which are spread upon the bare earth, and raising a disagreeable cloud of dust. The church is surrounded by a burying ground, already thickly tenanted. I saw some small graves, where lay sleeping some of the children of the pioneer missionaries.

We looked into some of the native huts, primitive enough in point of furniture; mats, and tapa in one corner for a bed, a few calabashes in another, hardly suggesting a pantry, were all. Their principal article of food is poi, a paste made of baked taro, which they eat with fish, often raw and seasoned with salt. It is the men’s employment to cultivate and cook the taro. Housekeeping I should judge to be a very light affair, the manufacture of mats and tapa being almost the sole employment of the women. There are no cold winters to provide for; the continuous summer furnishes food with but little labor, so that the real wants of life are met, in a great degree, without experiencing the original curse pronounced upon the breadwinner.

Such quantities of native presents as we have received today, from the natives coming in procession, each one bearing a gift! Among these were fish, lobsters, bananas, onions, fowls, eggs, and watermelons. In exchange, they expect us to shake hands and repeat aloha. Their childish exclamations of delight are quite amusing – as, for example, when they request us to turn around, so that they may examine our dresses and hair behind.

They all express themselves delighted in having a physician among them, and one man said, on being introduced to Dr.Judd, “We are healed.”

Her Royal Highness dined with us again today. She had been sending in nice things for the table all the morning, but did not seem quite satisfied, kindly inquiring if there was not something the strangers would like, not on the bill of fare. Mr. Bingham remarked, “You have been very thoughtful today.” She looked him in the face, and asked with an arch smile, “Ah, is it today only?” No mother’s tenderness could exceed hers toward Mr. and Mrs. Bingham. As she is an Amazon in size, she could dandle any one of us in her lap, as she would a little child, which she often takes the liberty of doing.

April 3, 1828. I visited some sick people with my husband – also called on Lydia Namahana, a sister of Kaahumanu. She is not so tall as her royal sister, but more fleshy. I should like to send home, as a curiosity, one of her green kid gaiters; her ankle measures eighteen inches without exaggeration. She is kind and good, and the wife of a man much younger than herself, Laanui, one of the savants of the nation, who assists in translating the Bible. Robert, a Cornwall youth, and his wife, Halakii, reside with these chiefs as teachers. They are exemplary Christians, and have been very useful. I am sorry to say that they are both quite ill of a fever.

Several captains from the whaling fleet have called on us today, who appear very pleasant and friendly. We have also received the compliments of Governor Boki (who was absent on our arrival), requesting an interview at his house at two o’ clock p.m. We shook the wrinkles from our best dresses, arrayed ourselves as becomingly as possible, and at the appointed hour were on our way.

The sun was shining in its strength, and we had its full benefit in the half-mile walk to the governor’s house. He met us at the gate and escorted us into the reception room in a most courtly manner. There we found Madam Boki, sitting on a crimson-covered sofa, and dressed in a closely fitting silk. She was surrounded by her maids of honor seated on mats, and all wrapped in mantles of gay-colored silk. I counted forty of them, all young, and some pretty. The room was spacious, and furnished with a center table, chairs, a mahogany secretary, etc., all bespeaking a degree of taste and civilization. Madam arose as we were individually presented by name, and curtsied to each. Mr. Bingham was presented with the governor’s welcome in writing, wh ich he interpreted to us as follows: “Love to you, Christian teachers, I am glad to meet you. It is doubtless God who sent you hither. I regret that I was at another place when you arrived. – Na Boki.”

I did not think he appeared very hearty in his welcome; time, however, will show. As this was our formal presentation to the magnates of the land, several speeches were made by those present. Kaahumanu presented hers in writing, as follows:

” Peace, good will to you all, beloved kindred. This is my sentiment, love and joy in my heart towards God, for sending you here to help us. May we dwell together under the protecting shadow of his great salvation. May we all be saved by Jesus Christ. – NA ELIZABETA KAAHUMANU.”

Governor Boki and lady visited England in King Liholiho’s suite in 1823. Kekuanaoa, husband of Kinau, a daughter of Kamehameha I, was also of the favored number received at Buckingham Palace. They would grace any court. The best looking man in the group was a son of Kaumualii, king of Kauai. He is a captive prince, as his father was conquered by Kamehameha I, and is not allowed to return to his native island. They all appear deeply interested on the subject of religion, and enter earnestly into every plan for the improvement of the people. The schools are under their especial patronage. Today Mrs. Bingham gave us an account of her first presentation at the Hawaiian court seven years ago. It was at the palace of Liholiho, before any of the natives had visited foreign countries. The palace was a thatched building, without floors or windows, and with a door but three feet high. His Majesty’s apparel was a few yards of green silk wrapped about his person. Five queens stood at his right hand, two of them his half sisters. After the three foreign ladies had been introduced, the king remarked to the queen nearest him, “These foreigners wish to remain in our kingdom, and teach a new religion. One of their peculiar doctrines is that a man must have but one wife. If they remain. I shall be obliged to send away four of you.” ” Let it be so,” was the prompt answer, ” let them remain, and be it as you say.” This was Kamamalu, who accompanied the king to England two years after, and died in London, whom, being the favorite, he retained as his only wife. The other four are happily married to men of rank. They are all of immense proportions, weighing three or four hundred pounds each. I have been silly enough in my younger days, to regret being so large; I am certainly in the right place now, where beauty is estimated strictly by pounds avoirdupois!

The natives are doing our six months’ washing. I have been at the stream to see them. They sit in the water to the waist, soap the clothes, then pound them with smooth stones, managing to make them clean and white in cold water. But the texture of fine fabrics suffers in th is rough process. Wood is scarce, being brought from the mountains, without the convenience of roads or beasts of burden.

Mrs. Charlton, wife of the English consul, and Mrs. Taylor, her sister, called on us today. They have been here but a short time, and are the only white ladies in the place, excepting those of the mission. Mrs. Taylor is particularly agreeable.

Visited again our sick friends, Robert and wife, and fear they are not long for earth, as they appear to be in the first stages of rapid consumption. On our way home we called on our friend Kaahumanu, and found her reclining on a divan of clean mats, surrounded by her attendants, who had evidentl y been reading to her. She was wrapped in a kihei of blue silk velvet. This kihei is a very convenient article, answering for both wrapper and bedspread, and is made of every variety of material. It is as easy here to take one’s bed and walk as it was in Judea.

Kaahumanu insists that we shall live with her; she will give us a house and servants, and I must he called by her name. We do not like to refuse, but the plan is thought to be impracticable, so we propose to have her come and live with us. She has a little adopted daughter, Ruth, whom she wishes me to take and educate as my own. There is certainly before us enough, and we need wisdom to choose wisely between duties to be done, and what is to be left undone.

In conversation with Mr. and Mrs. Bingham today, they related some anecdotes of our good queen-mother in former times. Quite a number of chiefs embraced the new religion, were baptized, and received into the Church, before this haughty personage deigned to notice the foreign teachers at all. It was after a severe illness, during which she had been often visited, and the wants of her suffering body attended to, that her manner softened toward them. The native language had been reduced to writing; a little book containing the alphabet, a few lessons in reading, and some hymns had been printed. Mr. and Mrs. Bingham took a copy of this little book and called on her one evening, hoping and praying to find some avenue to her heart. They found her on her mats, stretched at full length, with a group of portly dames like herself, engaged in a game of cards, of which they were passionately fond. This was the first accomplishment learned from foreigners, and they could play cards well before they had books, paper, pen, or pencil.

The teachers waited patiently until the game was finished; they then requested the attention of her ladyship to a new pepa (paper), which they had brought her. (They called cards pepa, the same word applying to books.) She turned toward them and asked,” What is it?” They gave her the little spelling book in her own language, explaining how it could be made to talk to her, and some of the words it would speak. She listened, was deeply interested, pushed aside her cards, and was never known to resume them to the day of her death. She was but a few days in mastering the art of reading, when she sent orders for books, to supply all her household. She forsook her follies, and gave her entire energies to the support of schools, and in attendance upon the worship in the sanctuary.

It is no marvel that Mr. and Mrs. B—- looked thin and careworn. Besides the care of her own family, Mrs. B—- boarded and taught English to a number of native and half – caste children and youths. Fancy her, in the midst of these cares, receiving an order from the king to make him a dozen shirts, with ruffled bosoms, followed by another for a whole suit of broadcloth! The shirts were a comparatively easy task, soon finished with the efficient aid of Mrs. Ruggles, who was a host in anything she undertook. But the coat, how were they going to manage that? They were glad to be valued for any accomplishment, and did not like to return the cloth, saying they had never learned to make coats. No, that would not do, so after mature deliberation, Mrs. Ruggles got an old coat, ripped it to pieces, and by it cut one out for His Majesty, making allowance for the larger mass of humanity that was to go into it. Their efforts were successful, and afforded entire satisfaction to the king, who was not yet a connoisseur in the fit of a coat.

A strange scene occurred in the church at the Wednesday lecture of this week. At the close of the usual services, nineteen couples presented themselves at the matrimonial altar, arranged like a platoon of soldiers. As I cannot understand much that is said, I must confine my observations to what I saw. One bride was clad in a calico dress, and a bonnet, procured probably from some half-caste lady who has a foreign husband. The groom wore a blue cloth coat with bright buttons, which, I am informed, is the property of a fortunate holder who keeps it to rent to needy bridegrooms. This coat is always seen on these occasions. Most of the brides wore some article of foreign origin; one sported a nightcap scrupulously clean, but a little ragged, abstracted, perhaps, from the washing of some foreign lady. Another head was bandaged with a white handkerchief, tied on the top of the head in an immense fancy knot, over which was thrown a green veil, bringing down the knot quite on to her nose, almost blinding the poor thing. The scene was so l udicrous I could hardly suppress laughter, especially at the response of ” Aye, aye,” pronounced loud enough to be heard all over the neighborhood.

There seems to be quite a furor for the marriage service. Mr. Richards, at Lahaina, says he has united six hundred couples in a few months. It is certainly a vast improvement upon the old system of living together like brutes, and it is to be hoped they will find it conducive to much greater happiness. The usual fee to the officiating clergyman is a few roots of taro, or a fowl, a little bundle of onions, or some such article for the table, to the value of twenty-five cents. Cheap matrimony this, even counting the cost of outfit or for the rental of clothes…

April 28, 1828. The grand annual exhibition of all the schools on this island is to be held at the church. Adults compose these schools, as the children are not yet tamed. The people come from each district in procession, headed by the principal man of the land (konohiki), all dressed in one uni form color of native cloth. One district would be clad in red, another in bright yellow, another in pure white, another in black or brown. The dress was one simple garment, the kihei for men and the pa-u for women.

It is astonishing how so many have learned to read with so few books. They teach each other, making use of banana leaves, smooth stones, and the wet sand on the sea beach, as tablets. Some read equally well with the book upside down or sidewise, as four or five of them learn from the same book with one teacher, crowding around him as closely as possible.

The aged are fond of committing to memory, and repeating in concert. One school recited the 103rd Psalm, and another Christ’s Sermon on the Mount; another repeated the fifteenth chapter of John, and the Dukes of Esau and Edom. Their power of memory is wonderful, acquired, as I suppose, by the habit of committing and reciting traditions, and the genealogies of their kings and priests.

As yet, only portions of the Bible are translated and printed. These are demanded in sheets still wet from the press. Kaahumanu admires those chapters in Paul’s epistles where he greets his disciples by name; she says, “Paul had a great many friends.”

The children are considered bright, but too wild to be brought into the schools. We intend, however, to try them very soon.